August 24, 2016

TRUMP'S HOPE IS THAT "IT AIN'T OVER UNTIL IT'S OVER"

ANALYSIS & OPINION BY RUSS STEWART

by RUSS STEWART

Yogi Berra, the late baseball player and master of malapropisms, once famously said, "It ain't over till it's over." That accurately describes the Clinton-Trump presidential contest, which won't be over for another 75 days.

There is a saying about weather that there is a lull before the storm. In politics, as August fades, we are in the lull before the lull before the Nov. 8 election. There will be a crystallizing moment some time in late October when the inert and vacillating 10 to 12 percent of the electorate finally makes a choice. That is the historical precedent.

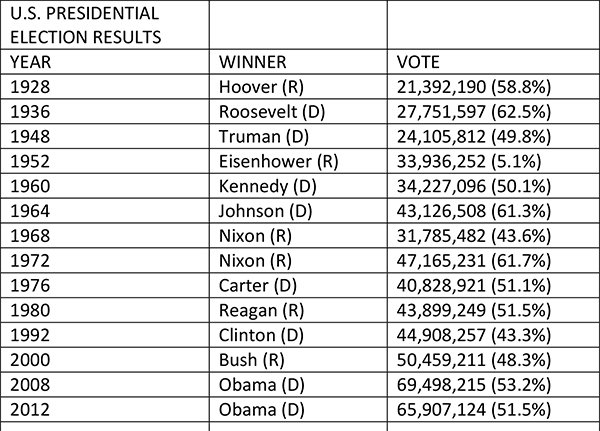

According to a compilation of tracking polls, Hillary Clinton is slightly ahead of Donald Trump, but not much beyond the 5 percent margin of error, and she is not over 50 percent. That's normal. Over the past century only three presidential candidates have gotten more than 60 percent of the vote: Franklin Roosevelt, with 62.5 percent in 1936, Lyndon Johnson, with 61.3 percent in 1964, and Richard Nixon, with 61.7 percent in 1971. Those were instances of incumbents trouncing flawed opponents.

As can be seen in the attached chart, each party has a built-in voter base of roughly 45 percent. It is the undecided 10 percent who are critical. For example, Barack Obama won by 69,498,215-59,948,240 in 2008, a 53-46 percent margin. John McCain, despite the economic downturn and anti-Bush revulsion, got the usual 45 percent Republican vote, but the "10 percenters" broke almost 80 percent for Obama. In 2012, despite some Obama fatigue, the president won 65,907,124-60,931,731, a 51-47 percent margin. His vote was off by four million from 2008, which means that about a quarter to a third of the "10 percenters" didn't vote, but Obama still got more than 60 percent of those who did. The Republican vote was up by less than one million.

So the mathematics of 2016 are simple. Trump will get 55 to 60 million votes, as will Clinton. It's the remaining 15 to 20 million voters who will decide the winner. If turnout is in the range of 130 million, Clinton will win; if it is in the range of 120 million or less, Trump can win.

However, this much is clear: early polls are meaningless. Decision making by 90 percent of the voters has already been done. The "10 percenters" decide in the last two weeks of the campaign. Here's an historical overview:

1936: After Republican Herbert Hoover defeated Irish-Catholic Democratic New York Governor Al Smith in 1928 21,392,190-15,016,443 (with 58.8 percent of the vote), it appeared that there was a permanent Republican majority, but the working class was becoming increasingly Democratic and big-city Democratic machines in Boston, New York, Cleveland, Detroit and Chicago made Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Michigan and Illinois competitive. The Great Depression of 1929 to 39, which was blamed on Hoover and ameliorated by World War II, gave the Democrats a permanent majority.

Seeking a second term in 1936, Roosevelt faced Republican Kansas Governor Alf Landon. Despite still-widespread unemployment, Roosevelt was given credit for trying to find solutions. However, a first-of-its-kind poll by a magazine called Literary Digest, wherein subscribers were asked to mail back an inserted coupon, showed Landon beating Roosevelt. All hell broke loose. Never mind that poor and unemployed people neither read nor subscribed to Literary Digest, thereby skewing the results. The poll energized the Democrats and made the Republicans complacent.

Roosevelt crushed Landon 27,751,597-16,679,583 in a turnout of 44,431,180. Roosevelt got about 12.7 million more votes than Smith got in 1928, Landon about 5 million fewer votes than Hoover, turnout was about 8 million higher, and the art of polling was discredited.

1948: The pollsters were back, namely, Gallup, Roper and Lubell, and by Labor Day they unanimously decreed that Republican New York Governor Tom Dewey was the next president. The Democrats had been in office for 16 years, the Republicans won control of Congress in 1946, and Harry Truman, Roosevelt's vice president when he died in 1945, was not accorded much respect. It was seen as over.

So certain was he of victory that Dewey campaigned languorously, delivered tepid presidential-sounding speeches, and avoided any controversies. Meanwhile, Truman got on a train, barnstormed across the country, ripped the conservative congressional Republicans, and energized the Democratic base, which still was the majority. Even though a Dixiecrat and a socialist took a combined 2,326,783 votes, Truman beat Dewey 24,105,812-21,970,066, getting 49.8 percent of the total cast and carrying Michigan, Illinois, Ohio and California while losing New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Even losing the pro-communist leftists, the Roosevelt-created "New Deal" coalition prevailed again. Turnout was 48,402,061, only about 4 million higher than in 1936.

The pollsters learned a lesson: keep polling to the end. A campaign can transform itself in the last two weeks.

1960: The media were now the message. After 8 years as vice president, Nixon consistently, albeit narrowly, led in the polls over John Kennedy, who was largely unknown until their first debate. That event, in which Kennedy was poised and cool and Nixon appeared swarthy and sweaty, reversed the trend. Nixon recovered somewhat, but he still lost 34,227,096-34,108,546, in part because of stolen votes in Illinois and his "get America moving again" theme. The Democrats' base was down to 50.1 percent. Turnout was 68,335,642, up 20 million from 1948.

1964: It was supposed to be contest between a clear-cut liberal (Kennedy) and a conservative (Barry Goldwater), but Kennedy was assassinated and Texan Johnson, benefiting from a wave of sympathy votes and his newfound pro-civil rights mantra, crushed Republican Goldwater 43,126,508-27,176,799. Goldwater did himself no favors with his "extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice" speech, but the Goldwater candidacy was a realigning event. He pushed nearly all of the few remaining white liberals and blacks out of the party, attracted the Southern state's righters, and proved that the party's low-water mark was about 40 percent, even with an unelectable nominee.

1968: It was a chaotic year, with assassinations, urban riots and a growing quagmire in Vietnam. Johnson quit, George Wallace ran, and the Democrats' Chicago convention was a fiasco. Early polls had Republican nominee Nixon beating Hubert Humphrey 2-1, with Wallace around 20 percent. Given Democratic divisiveness and defection, Nixon decided to play it safe, refusing to disclose a plan to end the Vietnam War. His mortal fear was that, just before the election, Johnson would unveil a peace plan and some settlement at Paris, thereby electing Humphrey.

That didn't happen, but Nixon's lead kept dwindling as old Democratic loyalties resurfaced. Nixon eked out a 31,785,480-31,275,166-9,905,473 win, getting 43.6 percent of the vote, to 42.9 percent for Humphrey and 13.5 percent for Wallace. Nixon got 4 million more votes than Goldwater got, and Humphrey got 12 million fewer than Johnson got. Had there been an "October surprise," or had the election been a week later, Nixon would have lost. Both parties' bases were now in the lower 40s.

1976: With Watergate, Nixon's impeachment and resignation, and Gerry Ford's pardon, how could the Democrats lose? Jimmy Carter almost did it, topping Ford 40,828,921-39,146,940, getting 51.1 percent of the vote. When the campaign began, newcomer Carter was leading Ford 2-1, and every week that lead shrank. As the election neared, American voters decided that Ford was not so bad after all. Carter got 11 million more votes than George McGovern got in 1972, and Ford got 8 million fewer than Nixon got. Clinton's hope is that, like Ford, she's "not so bad after all." Despite all the political turbulence, turnout in 1976 was 79,975,861, up 3.5 million over 1972.

1980: Few people thought Ronald Reagan would be elected president. In the 2 years before the election, nobody even thought about Reagan, but then came the oil crisis, record inflation and the Iran hostages. Carter became an object of ridicule and scorn, the worst fate a politician can suffer. For a while the media characterized the Carter-Reagan choice as "let the fools come in." Independent John Anderson was drawing 20 percent in the polls, but a crystallizing moment came about two weeks out: the hostages weren't home yet, Carter had to go, and Reagan was okay. Reagan won 43,895,248-35,481,435-5,718,437, getting 51.5 percent of the vote. Carter's vote dropped by 5.4 million from 1976.

1992: George Bush wasn't thought to be a bad president, wasn't corrupt or incompetent, but he just wasn't politically astute. Although the technically "won" the Iraq War and had stratospheric poll numbers in 1990-91, he still blew his re-election race, getting 39,102,343 votes to 44,908,257 (43.3 percent) for Bill Clinton and 19,741,085 (15.1 percent) for Ross Perot. How can an incumbent president, who got 48,881,221 votes in winning in 1988, lose 9.7 million votes in 4 years? Bush managed to rend asunder the Reagan coalition.

2016: Latest polls show Clinton ahead nationwide about 48-41 percent. She is winning by 5 to 8 percent in Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Virginia and New Jersey, and she already has been conceded Illinois, California, New York and Massachusetts. How can she lose? Ask Landon, Dewey, Nixon, Carter and Bush.

A Trump victory is unlikely, but it ain't over till it's over.

Send e-mail to russ@russstewart. com or visit his Web site at www. russstewart.com.